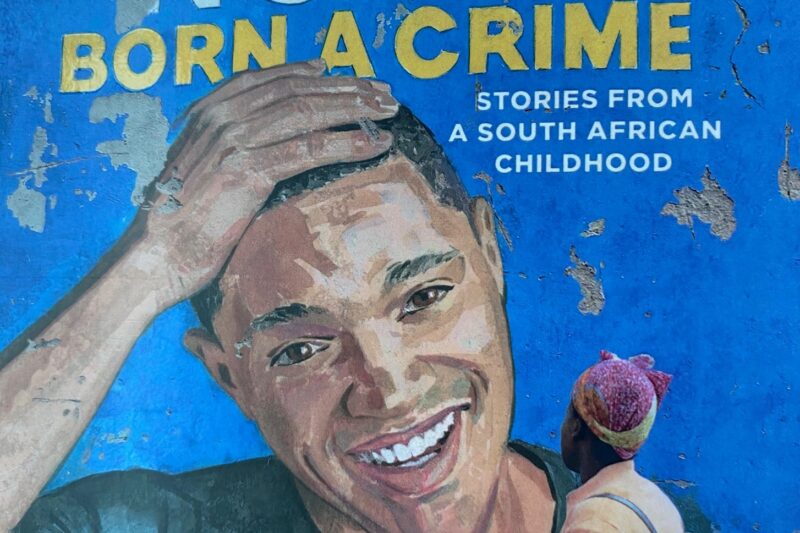

Trevor Noah came to my attention on Instagram. He’s the clever, funny and utterly engaging writer, political commentator, satirist and current anchor for The Daily Show when he replaced Jon Stewart in 2015. Time magazine has named this 36 year old African American one of the top 100 most influential people in the world. First published in 2017, The Wall Street Journal calls Born A Crime ” a book to read Now.” Tragically, in the context of George Floyd’s murder and race riots in the US this book is a timely read. A must read.

Born a Crime is not a political diatribe. It’s not a hammer head attack of ideas about the evils of apartheid. It’s not a ” this is what you should think” brute force of argument… and yet in its funny, matter of fact storytelling about a child’s view of growing up under apartheid we cannot feel anything but horror and disbelief that those in power can be so evil. This is a book of childhood memories and stories as its starting point but as the Guardian said, A remarkable memoir leavened with insight and wit, Born a Crime does more to expose apartheid-its legacy, its pettiness, its small minded stupidity and its damage- than any other recent history or academic text.

Don’t be scared of this book. At a time where many of us are overwhelmed by the pandemic, race riots and a world in crisis this book offers hope, humour and a testament to human resilience among the tragic stories of Trevor Noah’s life.

So what is Born a Crime about?

Let me walk with you into the first chapters. Trevor was born to a white German Swiss father and a black Xhosa woman in South Africa under apartheid. He was ” Born a Crime” because his mother was fined and imprisoned, under the Immorality Act of 1927 for having a ” carnal and illicit” relationship with a white man and producing a child classified as ” coloured.” He grew up with his mother and grandmother in Soweto.

” Where most children are proof of a parent’s love, I was the proof of their criminality. The only time I could be with my father was indoors. If we left the house he’d have to walk across the street from us. When I was a toddler my dad tried to go to a park with us but was walking a distance from us. I started chasing him screaming ” Daddy daddy!” people started looking. He panicked and ran away. I thought it was a game and chased after him. I couldn’t walk with my mother either. A light skinned child with a black woman would raise too many questions. There was a coloured woman named Queen who lived in our block of flats and mum would invite Queen to come to the park with us.Queen would walk next to me and act like she was my mother.”(p27)

In Soweto the risk of police taking kids away was very real. The wrong colour kid in the wrong colour area and the government would come in and strip your parents of custody and haul you off to an orphanage.

Why didn’t we just leave? Why didn’t we go to Switzerland? Trevor asks his mother. Because I’m not Swiss, she said stubborn as ever. This is my country. Why should I leave? “

There are stories about the 3 different churches he attended every Sunday. Then there’s, Sometimes in Hollywood movies they’ll have these crazy car chases where somebody jumps from a moving car. The person rolls around a bit, stops, pops up and dusts themselves off, like it was no big deal. Whenever I see that I think that’s rubbish. Getting thrown out of a car hurts way worse than that. I was nine years old when my mother threw me out of a moving car. It happened on Sunday. I know it was Sunday because we were coming home from church…..

Tribal conflict was another layer of tension in Trevor’s world, particularly as he was Xhosa and there was intense conflict with Zulu people. The schoolyard and navigating street life called for expert skills. Ever the strategist. he learned to navigate the complexity of his world by learning the languages of his oppressors. Trevor Noah speaks English, Zulu, Sotho, Tswana, Tsonga, Africaans, German and Xhosa fluently!

Tuesday nights the prayer meeting came to my grandmothers house and I was always excited for two reasons. One, I got to clap along to the beat for singing. and two, I loved to pray.My grandmother loved my prayers. She said they were more powerful because I prayed in English. Everyone knows Jesus, who’s white speaks in English. The bible came to South Africa in English. Which made my prayers the best prayers because English prayers get answered first. How do I know this? Look at white people. Clearly, they’re getting through to the right person!

There are stories of when his mother converted to Judaism, his early adventures in setting up schoolyard businesses, later doing business with crackheads in the hood, a place where life was cheap and tough and where people learned to be street savvy. The stories are littered with classic funny lines. Talking about food Noah writes, The ultimate upgrade was to throw on a slice of cheese. Forget the gold standard- the hood operated on the cheese standard. Cheese on anything was money.Cheese on a sandwich, cheese in the frig that meant you were living the good life. In any township in South Africa, if you had a bit of money, people would say “Oh you’re a cheese boy” In essence: You’re not really hood because your family has enough money to buy cheese.

I hope I’ve been able to give you a taste of this exquisite piece of writing and storytelling. The stories just keep rolling out, funny, incisive, unbelievable but true. It’s an essential read, especially in these times to remind us that for some human beings health care, education and decent housing is still equivalent to having that prized piece of cheese.